Later empires such as the Merovingian and Carolingian used the same title, expanding it to "count palatine", which meant an official sent to report on a remote region owned by the crown. Under the later German empire of the Saxon and Salian dynasties (919-1125), a further expansion occurred -- the counts palatine were now responsible for general administration and dispensing justice.

The regions along the middle Rhine were originally put under imperial control by the Salian dynasty. But after 1235, Emperor Friedrich II, who, more concerned with Italy than German lands, appointed a count-palatine of the Wittelsbach family which controlled the powerful duchy of Bavaria in return for the duke's support.

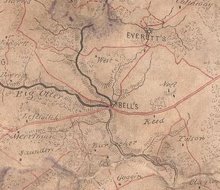

With the decline of the monarchy after Friedrich II, administrative rights reverted to local dukes or bishops, in Saxony, Bavaria and other places, but the count palatine of lower Lotharingia who headquartered at the palace at Aachen held onto these powers and kept them for his descendants, who called themselves the Counts Palatine of the Rhine. This territory, called the Rhenish or Lower Palatinate [German, Pfalz], was gathered on both sides of the Rhine River between the Main and the Neckar, with its capital at Heidelberg until the 18th century.

In 1329, to resolve an internal familial dispute, the North Mark of Bavaria was detached, named the Oberpfalz [Upper Palatinate], and transferred to the Count Palatine.

The trend in those days was to subdivide inheritance among all the sons of a family and in this way the Palatinate was divided into four regions in 1410. This was reversed by Friedrich the Victorious (1449-1476). After this event, the Palatinate's power grew and it became the leading state in the empire, a fact which was recognized by making its ruler an hereditary elector in 1356.

Previously an entirely Catholic region, the Palatinate accepted Calvinism under Elector Friedrich III during the 1560s.

Elector Friedrich V's acceptance of Bohemia's offer of its crown touched off in 1618 the Thirty Years War, a complicated catastrophe from which the Palatinate never really recovered. Although the final result was centuries in coming, it meant that instead of politically leading Germany, the Palatinate became a spoil, fought over by other states and countries. Subsequent German history might have been considerably different had the Palatinate rather than Prussia held the position that the latter was to acquire for itself. Initially however, the only immediately apparent loss was that of the Upper Palatinate which was claimed by Bavaria.

During these times, a weakened Palatinate was no match for an ebullient France under Sun king Louis XIV, whose forces ravaged the region. In fact, so much international concern was there over growing French hegemony, that Britain led a coalition of powers to oppose her. These struggles became known as the War of the Palatinate (or the War of the Grand Alliance or War of the League of Augsburg, 1688-1697). One major effect was large scale emigration from 1689 to 1697, and later, giving rise, for example, in the United States to the phenomenon of the Pennsylvania Dutch.

There was a major freeze in the winter of 1708/09 in the Palatinate. On 10 January 1709 the Rhine River froze and was closed for five weeks. Wine froze into ice. Grapevines died. Cattle died in their sheds. Many Palatines traveled down the Rhine to Rotterdam in late February and March. In Rotterdam they were housed in shacks covered with reeds. The ones who made it to London were housed in 1,600 tents surrounding the city. Londoners were resentful. Other Palatines were sent to other places, such as Ireland, the Scilly Isles, the West Indies, and New York.

Queen Anne was related to the ruler of the Palatinate. On 24 March 1709 a British naturalization act was passed whereby any foreigner who would take the oaths to the British government and profess himself a Protestant would be immediately naturalized and have all the privileges of an English-born subject for one shilling.